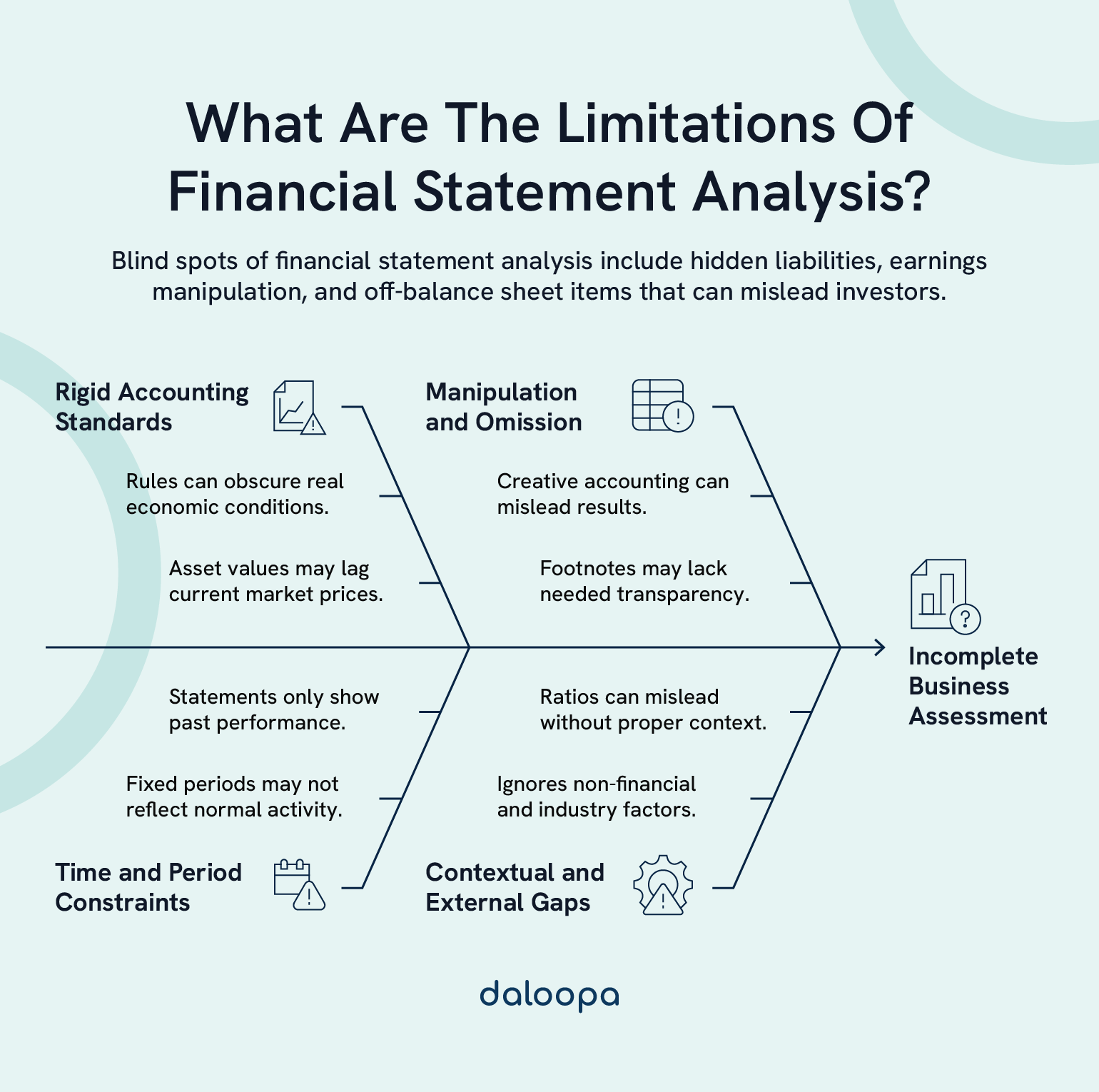

You trusted the numbers—and missed the warning signs. Here’s why that happens.

Financial statement analysis is a powerful tool for assessing a company’s health, but it’s not infallible. Financial statements are rooted in historical data and shaped by accounting rules that can mask deeper issues. They don’t capture shifting market trends, management competence, or company culture. Relying too heavily on the numbers can lead to costly blind spots. To assess a business accurately, you need to understand the limitations of financial statement analysis and know what it leaves out.

Key Takeaways

- Financials show the past, not necessarily what’s happening now or what’s next.

- Accounting rules can obscure operational realities and economic substance.

- A full view demands pairing metrics with real-world context and qualitative insight.

Inherent Constraints in Financial Reporting

Evaluating company financial health requires a clear-eyed understanding of how financial statements are constructed—and where their blind spots lie.

Public company financial statements are bound by structural and methodological limits that can distort or obscure the company’s actual position. These limits come from established rules, timing lags, and the challenge of estimating future-dependent figures. These are some of the key limitations of financial statement analysis that professionals must keep in mind.

Accounting Framework Limitations

Accounting standards require companies to follow formal rules, which can reduce the flexibility needed to show true business economics.

Inventory accounting, for example, can look very different under LIFO compared to FIFO, shifting earnings and asset figures depending on method selection. This is especially true in times of inflation. A retail chain using LIFO during rising prices may show lower profits and tax liability. Yet it will look less profitable to an untrained eye than its FIFO-reporting competitors, another example of the limitations of financial statement analysis in practice.

Assets recorded under the historical cost rule may be out of sync with their present market value. This is especially significant for long-held assets and intangibles, where book values can be decades behind economic realities.

Think of long-held real estate in rapidly growing cities. Properties purchased decades ago might sit on the books at a tenth of their current value. That disconnect can lead to gross undervaluation, missed investment, or poor internal decision-making, an important consideration when evaluating company financial health..

Temporal Constraints

By design, financial reports represent only fixed timeframes, creating a mismatch between business operations and the statements that describe them. This is one of the fundamental limitations of financial statement analysis.

A balance sheet captures financial status at a single moment. That moment, say, the end of a fiscal year, might not represent normal business activity or typical liquidity patterns.

Revenue recognition rules can also distort timing. One big sale or an end-of-year contract may inflate earnings for that period but not reflect ongoing business pace or customer behavior.

Look at retailers like Target whose year-end cash balances are often inflated due to the post-holiday sales surge. Without that context, an investor might assume liquidity health that doesn’t exist in other months, again underscoring the limitations of financial statement analysis.

Measurement and Estimation Issues

Behind many financial statement figures are estimates, not hard numbers, introducing room for interpretation, inconsistency, or error. This is a critical reason why savvy professionals always consider the limitations of financial statement analysis when interpreting results.

Reserves for uncollectible accounts, depreciation methods, and inventory write-downs all hinge on judgment calls. These decisions directly shape bottom-line results and asset values. If a company underestimates bad debt, like many banks did ahead of the 2008-2009 financial crisis, it delays recognition of risk and paints an unrealistically stable picture. When reality hits, it’s often too late. Investors lose money, and trust evaporates.

Valuing intangibles and complex instruments is even trickier. These often depend on market conditions or future outcomes, which are hard to forecast with precision. WeWork, once valued in the tens of billions, had vast intangible assets based on projected growth and brand strength. Until market sentiment shifted.

When management assesses long-term assets for impairment, their forecasts can swing the reported numbers considerably, sometimes with a heavy bias toward optimism. When things go south, those numbers don’t just quietly adjust, they crash, dragging reputation and investor confidence down with them.

Manipulation and Interpretation Challenges

Getting clean, useful insights from financials isn’t always straightforward. Discerning between fair representation and financial smoothing tactics requires both skepticism and context. And when that skepticism is missing? The consequences can be brutal, from flawed decisions to financial disaster. These risks highlight why the limitations of financial statement analysis must always be factored in.

Creative Accounting and Earnings Management

Some firms use accounting flexibility to brighten their reports, shifting numbers in ways that meet expectations without breaking rules.

Take WorldCom, for instance, which fraudulently capitalized operating costs to inflate profits. Or GE, once the poster child for stable earnings, later investigated for smoothing its results with perfectly timed asset sales and aggressive revenue recognition. Sometimes these practices don’t always look illegal. They often just look “optimistic.” But they create a house of cards, one quarterly report at a time.

Revenue might be pushed forward or expenses delayed to polish the bottom line. Gains from asset sales may be timed to fill earnings gaps, giving an inflated sense of profitability. Sometimes these numbers still pass audits and meet the rules, but they don’t reflect the reality investors or stakeholders need to see.

Signals that something’s off include:

- Shifts in accounting policies with little explanation

- One-off transactions clustered at reporting deadlines

- Gaps between earnings and actual cash movements

- A history of report restatements

Disclosure Inadequacies

Financial reports often fall short in the details they offer, especially in the footnotes, where the real nuance usually lives. When disclosures are weak, stakeholders are left to make decisions in the dark.

Vague or missing disclosures are common in areas like:

- Deals involving related parties

- Potential future liabilities

- Contracts or debts not listed on the balance sheet

- Valuation methods for complex assets

One good example in regard to potential future liabilities is the case of BP, which didn’t fully reflect its Deepwater Horizon oil spill exposure until it was far too late.

The narrative quality in these notes can differ dramatically between firms, making apples-to-apples comparisons tough.

Analytical Interpretation Pitfalls

Raw financial numbers don’t interpret themselves. They only gain meaning when viewed alongside business context, sector norms, and company-specific details.

Consider the influence of:

- Seasonal shifts in sales or expenses

- One-off gains or losses

- Policy changes in revenue recognition

- Industry-specific success factors

Even with the same data, different analysts can draw sharply different conclusions, depending on the models and assumptions they bring to the table. This subjectivity is one of the enduring limitations of financial statement analysis. Ask ten analysts what a P/E ratio means, and you’ll get twelve opinions and a headache.

Ratio Analysis Limitations

Ratios simplify financial data into bite-sized indicators, but even these can mislead if used in isolation or without context.

Ratios only capture one point in time and can miss changes that unfold gradually or events that just happened after the report date.

Comparing across industries or even across companies becomes complicated when accounting practices, fiscal calendars, or business models differ significantly. The use of financial statements comparison tools can help, but these, too, must be interpreted with care.

And some of the most important business strengths, like a company’s brand strength or ability to innovate, don’t show up in standard ratios.

Contextual and External Factors

Even the clearest set of financials is incomplete without a broader perspective. Business outcomes are shaped by what’s happening in the market, the economy, and behind the scenes at the company. Ignoring this is one of the biggest limitations of financial statement analysis.

Industry and Competitive Context

Evaluating company financial health depends heavily on industry context. In fast-moving sectors, a company may carry more debt to fuel expansion, while in stable markets, the same debt load might raise red flags.

Consider Netflix in its growth phase. It carried significant debt to fund original content, a move that would’ve seemed reckless for a legacy media house. But in the context of its market dominance and subscriber growth, it was a calculated play.

Factors like regulation, competitive intensity, and disruptive technologies shape how numbers should be interpreted. A firm’s patents or customer loyalty can make average numbers look better or worse depending on the strategic backdrop.

That 15% profit margin? A standout in retail, maybe middling in enterprise software. Context defines performance and misreading it can mean betting on the wrong horse.

Economic and Market Conditions

Big-picture economic forces often explain performance trends that might otherwise seem puzzling.

Interest rate changes affect financing costs and capital projects. Inflation shifts both cost inputs and pricing power. Currency swings reshape revenues and expenses for global firms. When the Turkish lira plunged in 2018, multinationals with operations there saw their earnings take a hit, even though their underlying performance hadn’t changed. Financials showed the symptoms, not the cause.

Different regions often produce different outcomes, even within the same company. A firm might excel in fast-growing markets while stagnating in regions facing economic headwinds. That divergence may point to smart regional strategy or unaddressed weaknesses.

Non-Financial Performance Indicators

Non-financial metrics help fill in the picture where traditional statements fall short. Using financial statements comparison tools alongside qualitative indicators like customer loyalty, employee engagement, and operational efficiency say a lot about future performance.

Spending on innovation, strength of intellectual property, and pace of product development often indicate whether today’s earnings will hold up or grow in the years ahead. If Blockbuster had tracked innovation investment more closely, or if investors had looked beyond revenue, they might have seen the cracks forming long before Netflix came knocking.

Operational stability also hinges on strong vendor relationships and a reliable supply chain, while ESG factors now play a growing role in investor evaluation.

Strategic Alignment Assessment

Looking at strategy alongside financials tells us whether a company’s numbers reflect well-placed bets or shortsighted moves.

How leadership allocates capital shows priorities—growth, stability, or risk. A deep bench and proven track record help signal whether those bets are likely to pay off. When Apple shifted focus to services over hardware, its investment strategy, reflected in rising R&D and acquisitions, matched a shift in vision. The result? A more diversified, future-proofed revenue stream.

Shifts in revenue streams or profitability often hint at evolving business models. Partnerships and acquisitions can confirm or challenge the logic of long-term strategy.

Beyond the Numbers: Reading Financial Statements with a Clearer Lens

Financial statements offer great insight, but they’re only part of the story. As we’ve seen, limitations in accounting rules, timing, estimations, and even deliberate manipulation can cloud the picture. Ratio analysis and financial statements comparison tools might give a quick snapshot, but without context like industry trends, macroeconomics, leadership strategy, and non-financial indicators, it’s easy to misread the signs when evaluating company financial health.

A 15% profit margin might shine in one sector and fall flat in another. Massive revenue could mask weak cash flow or fragile strategy. In short, the numbers speak, but they don’t explain themselves.

That’s where Daloopa comes in. It automates the tedious, manual work of financial modeling so you can spend less time gathering data and more time analyzing it, spotting red flags early, and making smarter investment decisions.

Try Daloopa and see how much faster and sharper your analysis can be. Book a demo today.